[ad_1]

Ralph Knibbs defied the experiences of childhood racism to become a rugby star, dine with Muhammad Ali and inspire a generation of black players.

Knibbs famously rejected the chance to fulfil his dream of playing for England twice. That in itself makes the Bristol hero unique. But it also tells barely half the story of the former centre’s inspirational and defiant journey.

‘I grew up in Bristol and spent my first years of senior school in Knowle West, the same area of the city that Ellis Genge comes from,’ says Knibbs.

‘In the 1970s, it was a whitedominated council estate. There were only a handful of black families in the area. It was about survival. The reality was people would do anything to get the black families to leave. We had human faeces put through our front door.

‘They’d write n***** on the walls. Experiencing that at a very young age made me question why I was black. I just wanted to be like everyone else. Lots of black families moved out.

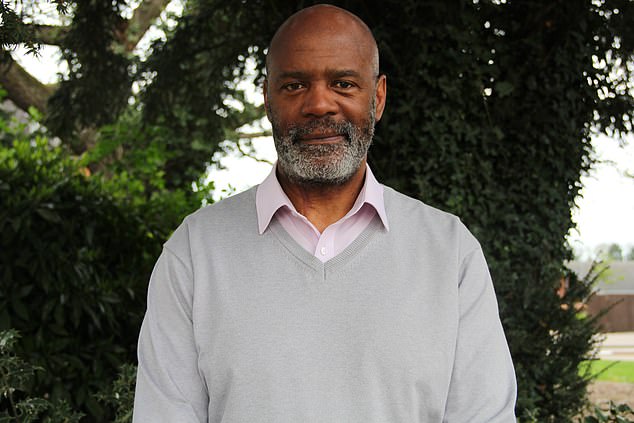

Ralph Knibbs famously rejected the chance to fulfil his dream of playing for England twice

Knibbs experienced racism as a youngster and is now advising the RFU on diversity

‘But it was bizarre because while it was incredibly tough, once you’d survived the attacks the community almost adopted you. It was very strange.’

Those experiences drove Knibbs forward and he toughened up quickly. Rugby became his safe haven though, cruelly, the sport did not always embrace him.

Despite setbacks, Knibbs went on to score 122 tries in 436 games in a 15-year Bristol career.

Today, while working for UK Athletics, he uses his experiences to advise the RFU on diversity and inclusion to broaden English rugby’s social reach.

‘I had a final England Schools trial at Under-16 level, but didn’t make it,’ Knibbs says. ‘I was one of only two boys to turn up from a comprehensive school and the only black boy.

‘I played really well. At the trial, we were asked to say which school and club we were from and I answered truthfully.

‘When I was told I didn’t get in, I was advised to lie next time and say I came from Bristol Grammar. I was proud of where I came from, but I was told by the selectors to hide it. That’s a good example of what it was like at the time.

‘It had such a huge impact on me that I considered packing rugby in. I thought it was all so unfair.’

Knibbs — who grew up idolising West Ham’s Clyde Best because he was one of the few black sport stars in England — fought back against the system.

In 1982, aged only 17, he made his Bristol debut and scored with his first touch.

‘While my upbringing was very difficult, it helped me,’ Knibbs says. ‘I went from being very shy and not wanting attention to someone who could go on the rugby pitch and express myself. As a young black boy in Knowle West, any attention was bad attention. Suddenly, I realised I was quite good at rugby and it got me some good attention!

‘Rugby gave me a confidence to deal with being the only black player on the pitch. I could just be me on the field at a time when it was difficult to do that in society.’

Knibbs played in rugby’s amateur era, combining his playing career with different jobs. October marks Black History Month and his story is certainly worth celebrating. It is one which will surely help and inspire others too.

His sons Harvey and Alex both work in sport. Harvey is a footballer for Reading, while Alex is an athlete who specialises in the 400m hurdles.

In 1984, Knibbs was selected for England’s tour of South Africa. But he turned down the call due to the apartheid regime.

‘I was only 18 and hugely out of my depth,’ he recalls. ‘It was always my ambition to play for England, but it didn’t feel comfortable for me to tour South Africa.

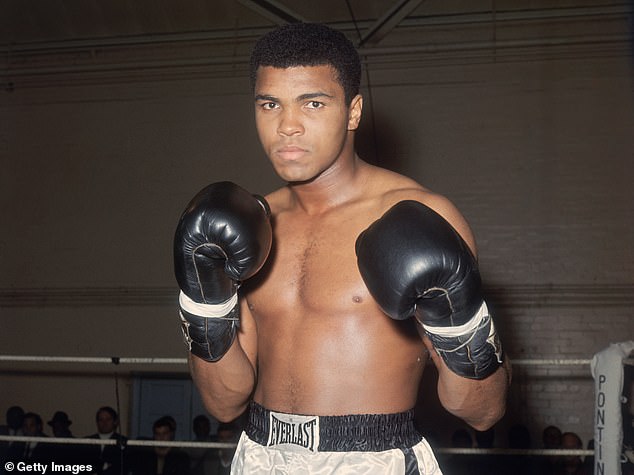

Knibbs was invited to a dinner with Muhammad Ali, which was an incredible experience

‘I was given time to consider it, but I decided if I went I would be seen to be supporting the apartheid regime. Nelson Mandela was in prison. I was told if I did go, I’d have to have my own bodyguard. I was told if I was separated from the rest of the England team, I’d likely be shot. That brought home the starkness of the situation.

‘We received lots of phone calls at our family home about my decision from people we didn’t know. Their views were divided.

‘Some said if I’d been on the pitch as a black man next to the Springboks, that would have been a really powerful image. They said it could have given the nation hope.

‘I hadn’t thought of it like that, but I was very comfortable with the decision I made. I’d do the same thing again.

‘On the back of the decision, I was invited to a dinner with Muhammad Ali. I was sat on the top table with him. He’d heard about my story. I sat there with my mouth open most of the time.

‘Ali said to me, ‘Are you crazy? I’ve seen American Football but you rugby guys don’t have pads! How do you do it?’.’

Four years later, Knibbs was asked to play for England again. The answer was the same, but the decision was far simpler.

‘It was a last-minute call-up and my employer wouldn’t give me the time off,’ Knibbs says. ‘I was told I’d be sacked if I went on tour.

‘It was as simple as that. England weren’t going to pay my mortgage! I wasn’t even allowed unpaid leave.

‘I was told by England’s hierarchy: ‘We’ve asked you twice now to play for England. I can assure you there won’t be a third time’.

‘It might sound perverse, but I think it was a good thing. I’m not sure England was ready for me!

‘I’d carry the ball like a basketball, hold it in one hand and do no-look passes behind my back. England would have wanted to put me in a straitjacket.

‘I’d have loved to have won a cap and the fact I didn’t still rankles, but I feel privileged to have been able to play the sport.’

Ralph’s son Harvey (right) is a footballer for Reading and his other son Alex is an athlete

Knibbs, now 60, was honoured this year at the Rugby Black List awards for his contribution to improving the game’s diversity. It is something he continues to do.

‘It’s brilliant to see the strides rugby has made, but we can still do more,’ Knibbs says.

‘It’s great to look at the England sides and the 10 Premiership teams now and see players of different colours.

‘When I speak to young black players of today, they don’t realise what we went through in the past. Maybe that’s because I don’t tell my story enough.

‘What we’ve tried to do with the RFU is give the clubs little tips on how they can open their doors and be more diverse. That’s why the Rugby Black List is so important.

‘It’s something I’ll never stop working on because of what I experienced.’

[ad_2]

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source link