[ad_1]

A lawsuit from Ozy accuses Ben Smith of killing the company only to steal its business model for Semafor.It alleges Smith violated an NDA by disclosing trade secrets from a failed BuzzFeed merger.It says Smith sabotaged Ozy as a Times columnist, then created “Ozy 2.0” with his outlet Semafor.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you’re on the go.

download the app

By clicking “Sign Up”, you accept our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can opt-out at any time by visiting our Preferences page or by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of the email.

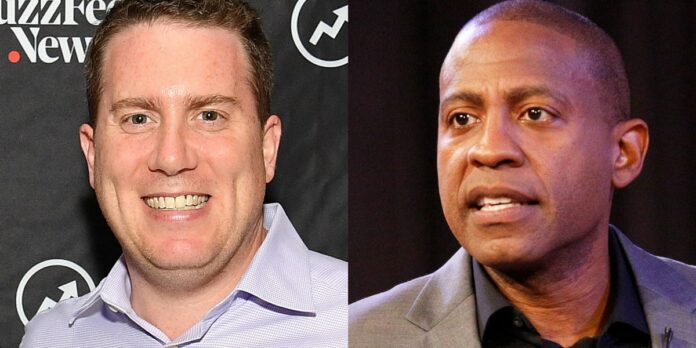

Did Ben Smith sabotage Ozy only to plunder its ideas for Semafor?

That’s the question at the heart of a lawsuit filed Thursday morning in Brooklyn Federal Court alleging that Smith, the Semafor cofounder and former editor in chief of BuzzFeed News, violated a nondisclosure agreement and stole trade secrets from Ozy in order to build his own media company.

The lawsuit — filed by Ozy Media against Smith, Semafor, and BuzzFeed — portrays Smith as improperly acting as a media columnist and aspiring mogul at the same time.

It claims Smith was a major player in an ultimately unsuccessful 2019 merger between BuzzFeed and Ozy, used NDA-protected information from those talks to assassinate Ozy in a series of articles for The New York Times, and then replicated Ozy’s investor and revenue strategies for his own media company.

“Ben Smith did not just take the proverbial page out of the OZY playbook: he took the entire playbook,” the lawsuit alleges.

Smith, reached by phone, said he’d decline to comment, “obviously.”

A BuzzFeed representative also declined to comment.

Justin Smith, a Semafor cofounder, didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Smith’s reporting led to Ozy’s implosion

Founded and led by the media entrepreneur Carlos Watson, Ozy launched in 2013. By 2020 it had raised $83 million from investors including Marc Lasry, Laurene Powell Jobs, and Ron Conway. Axel Springer, which owns Business Insider, was also an investor.

Watson, the face of the company, landed interviews with high-profile figures including Bill Clinton and Trevor Noah; hosted its signature live event, Ozy Fest, in New York City; built what he described as a robust newsletter operation; and struck deals with streaming services.

A series of articles by Smith, who joined the Times as a media columnist after leading BuzzFeed’s news division, sparked Ozy’s collapse.

In a September 2021 article, Smith reported that Samir Rao, Ozy’s cofounder and chief operating officer, impersonated a YouTube executive in a meeting with investors at Goldman Sachs — actions that would later lead to a federal prosecution against Watson and a guilty plea from Rao. Smith also reported on claims that Ozy had wildly inflated its audience numbers in public statements. In one column he likened Ozy to the notorious blood-testing company Theranos.

Advertisers and investors left Ozy in droves. Ozy ended its operations and laid off its entire staff, many of whom described internal doubts about the company and a breakneck workplace culture. The Securities and Exchange Commission, investors, and insurers sued the company. Attempts to revive the company, in 2022 and 2023, floundered.

In early 2023, federal prosecutors in Brooklyn indicted Watson and Ozy Media, alleging that he conspired to impersonate media executives while courting investors and lenders and that the company broke financial laws by misrepresenting its financial results, debts, and audience size.

Watson speaking at a panel at Ozy Fest in 2018.

Brad Barket/Getty Images for Ozy Media

The indictment, Ozy’s new lawsuit says, was “largely parroting the false accusations levied in Ben Smith’s reporting.”

In court filings, Watson has defended his actions as “at worst commonplace puffery” and alleged that the federal prosecutors went after him because he’s Black. A federal judge has since ruled that the prosecutors ran afoul of a rule barring them from making statements about a defendant’s character when they referred to Watson in a press release as a “con man.”

That criminal case is scheduled to go to trial in May, court records show — with Rao as a likely cooperating witness.

Ozy’s Thursday lawsuit — brought by Dustin Pusch, one of the attorneys who drove Dominion Voting Systems‘ defamation lawsuits against right-wing media companies that peddled lies about the 2020 election — puts the blame for Ozy’s and Watson’s woes at Smith’s feet.

Related stories

As majority owner of what’s left of Ozy, Watson would be the beneficiary of any damages, but he’s not named as a plaintiff because the lawsuit is about the NDA, to which he is not a party, Pusch told Business Insider.

“Basically at this point Carlos is OZY,” Pusch said.

“But from a legal standpoint the contract with Ozy was with BuzzFeed, and the trade secrets themselves were also OZY’s,” he said. “If we had sued for defamation we would have named Carlos as a plaintiff, but the crux of the Times stories are time-barred,” meaning too old to legally be sued over, Pusch added.

Smith was deeply involved in BuzzFeed-Ozy merger talks, the lawsuit says

In disclosures included in his articles for the Times, Smith said he was only “peripherally involved” in acquisition talks between Ozy and BuzzFeed. But the lawsuit suggests his role was much deeper.

In August 2019, when BuzzFeed CEO Jonah Peretti was looking for merger opportunities, Smith met with Watson and “took Watson’s temperature on a willingness to sell his company,” the lawsuit says.

The following month, the two companies signed a nondisclosure agreement — Rao signed on Ozy’s behalf and Peretti for BuzzFeed, a copy reviewed by Business Insider shows — to allow Ozy to start disclosing confidential internal information so that BuzzFeed could evaluate the company.

Court filings do not indicate whether Smith was aware of the document, but the contract holds BuzzFeed “responsible for any breach of confidentiality by its respective employees and agents.”

By January 2020, BuzzFeed had offered to buy Ozy for $300 million and make Watson the company’s president, the lawsuit says.

Watson rejected the offer, the lawsuit says; he believed BuzzFeed needed Ozy more than Ozy needed BuzzFeed. Watson also believed Smith didn’t really want him as his boss, the lawsuit says.

“Watson sensed Smith’s discomfort with the idea of a joint OZY-BuzzFeed venture,” the lawsuit says. “Smith seemed to have a particular difficulty with the idea that Watson would be made President of and a Board Member for the joint venture, and that Smith would have to answer to both Watson and Peretti.”

The following month, Smith decamped from BuzzFeed to the Times. The lawsuit alleges that in his reporting about Ozy, Smith violated BuzzFeed’s NDA.

The lawsuit says that when Watson raised the issue with an editor at the Times before it published his first story about Ozy, the editor brushed away concerns and said that “she was outside of the city and could not dig into the issues before publication.”

A representative for the Times didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. In 2022, Ben Smith left the Times to build Semafor with the former Bloomberg Media CEO Justin Smith, who isn’t related to him.

The lawsuit claims Semafor is ‘Ozy 2.0’

Central to the lawsuit is the claim that Semafor’s pitch appeared novel but was actually “a spitting image” of Ozy Media.

The lawsuit says Semafor “reverse engineered” Ozy’s strategy of mixing events, podcasts, subscription newsletters, and video operations to effectively create “Ozy 2.0.”

In fact, many established and upstart media companies, from the Times to 2011-founded Vox Media (and, to be sure, Business Insider), were at the time adopting a similar playbook of revenue diversification by distributing their content on platforms including digital video, email newsletters, and live events.

At launch, Semafor presented itself as a publication for educated, global readers that would break news, present new kinds of storytelling, and emphasize individual reporters. It was compared to publications like Axios and Vox because of its efforts to be transparent and improve readability, and it was said to import Smith’s well-established scoop-driven approach.

Ozy promoted itself at launch as a media company for curious people interested in change and ideas, with a focus on emerging business and cultural figures.

The suit also makes the case that Smith tried to replicate Ozy’s investor support. It cites Powell Jobs of the Emerson Collective several times, boasting that she was one of Ozy’s earliest investors and that she turned away opportunities to invest in BuzzFeed.

Her media investments weren’t unique to Ozy, though. Steve Jobs’ widow was also known to back many companies in media, Hollywood production, and digital nonprofit news, including the venerable magazine The Atlantic, Axios, and the studio Anonymous Content. She later retreated from funding some of those ventures.

As it happened, Powell Jobs never invested in Semafor, though the Smiths approached Emerson Collective about investing, Axios reported. The lawsuit claims people “close to Powell Jobs” put any money into the company.

[ad_2]

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source link