[ad_1]

A look at the different roles played by members of a rugby team and what skills they need

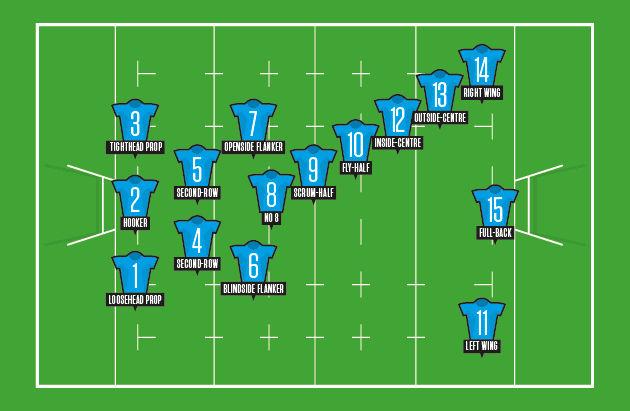

Every position in rugby union has a different role to play on the field. A starting team consists of 15 players – seven backs and eight forwards – and unlike in football where managers can adjust formations at will, all rugby teams have the same mix of props, hooker, locks, back row forwards, half-backs, centres, wings and full-back. Each position has a unique job description and skillset.

Here we run through all the positions in rugby union – including the replacements bench – and explain each player’s responsibilities in the team. We also highlight some of the best players ever to have plied their trade in each berth.

BACKS

Full-back (Number 15)

Full-back is no place for the faint-hearted as the player in the number 15 shirt is a team’s last line of defence, much like a sweeper in football cleaning up the mess. Tackling is a must, and – along with the wingers – they’ll be the player who takes the majority of the high balls. The likes of Leigh Halfpenny, Rob Kearney and Freddie Steward these days, made a living out of their high-ball mastery but that’s not all they have to do.

The full-back is expected to be a good kicker, handy enough to deal with the 50:22 law, and be an attacking threat. Christian Cullen, the great All Black, was one of the best attacking full-backs ever to play the game, and the sight of hitting the attacking line at speed or running from deep is enough to bring opposition players of his era (1996-2003) out in cold sweats.

Wing (Numbers 11 and 14)

Of all the positions in rugby union, the wings are the glory hunters, seeing as their currency is tries. There is much more to being a modern wing than getting on the end of a backs’ move and touching down in the corner, however.

Defence, courage under the high ball, intelligent reading of the game and working with the full-back in the backfield are all part of it. Jason Robinson (one of England’s best ever players) has a highlights reel of tries to rank with anyone but he could defend and kick with the best too.

The wings shouldn’t just hang about waiting for the ball. A good winger comes off their touchline and runs off the shoulder of attackers. All-time Premiership top scorer Chris Ashton did this for years, running rugby league lines – many of them didn’t come off, but when they did he was in business.

Japan head coach (and former England and Australia boss) Eddie Jones has a theory about most things, and he has one about wingers. He’s traditionally liked his teams to feature a work-rate winger (a Jack Nowell, for example) and a speed merchant (an Anthony Watson or a Jonny May). And when he was in charge of Australia he didn’t mind a couple of big wings either, such as Wendell Sailor and Lote Tuqiri. Wingers can come in all shapes and sizes, from Wales’ all-time top scorer Shane Williams (5ft 7in, 12st 8lb), to Fiji’s Nemani Nadolo (6ft 5in, around 19st).

Centre (Numbers 12 and 13)

The inside-centre (number 12) can usually be one of two beasts. Does the coach want a big basher who will get over the gainline, like Manu Tuilagi, or a ball-playing 12 in the Owen Farrell or Matt Giteau mode? Occasionally you get both in the same package like Ma’a Nonu in his later days for New Zealand.

A good kicking game to take the heat off the fly-half is a massive plus – indeed, Kiwis often refer to the inside centre as the “second five-eighth” (the fly-half being the first).

The number 13 – the outside-centre – should possess a good outside break, kicking game and vision, but it is also one of the hardest places to defend from in the backline. For 12s and 13s good defence is non-negotiable.

The 10-12-13 axis is generally referred to as the midfield.

HALF-BACKS

Fly-half (Number 10)

The fly-half is the general of the team and, normally, the key decision-maker in attack. They are often also the team’s main goalkicker, and – as was the case with Johnny Sexton – frequently the eyes and ears of the coach on the field

In virtually every attack the fly-half will get their hands on the ball and either kick or pass. Most of them will call back-line moves and probe for gaps in the defence, and they will liaise with the lineout forwards, telling them where they want the ball to launch attacks.

Some other backs might try drop-goals but the fly-half is the biggest source of this much overlooked way of scoring. New Zealand were searching for a three-pointer in the late stages of the 2007 Rugby World Cup quarter-final against France in Cardiff but both their main fly-halves, Dan Carter and Nick Evans, were off the pitch. They failed and lost 20-18.

It used to be accepted that the fly-half did not bother tackling but that all changed when Jonny Wilkinson burst onto the scene, and burly opposing centres and back-rowers tried to run down his channel – usually they didn’t try again. Number 10s now tend to come in all sizes, from Marcus Smith to Handré Pollard.

Scrum-half (Number 9)

The scrum-half is an extremely important position in rugby union, as they’re the link between the forwards and the backs. They’re traditionally good communicators who can tell players twice their height and weight what to do, are almost always in the ear of the referee, and are generally a bit chippy. They are not always small though; Terry Holmes and, more recently, Mike Phillips were as big as back-row forwards.

Quick passing, off both hands, is one of the mainstays of a scrum-half’s skill-set, as is the dreaded box kick and an eye for a gap around the breakdown. If you are Antoine Dupont you can add running support lines off midfielders and wingers into the mix.

Scrum-halves have to be among the fittest players on the pitch. They need to get to every ruck and maul, and can expect to run over 10km a game if they stay on for the duration. Somewhat bizarrely, however, despite being one of the key decision-makers in the team and part of the so-called spine, they seem to get subbed off after an hour or so most weeks.

FORWARDS

Prop (Numbers 1 and 3)

Along with the hooker, the two props form the front row of the scrum. There are different types of prop: loosehead, tighthead and the rare beasts who can play both sides – take a bow Andrew Porter, Jason Leonard and Fran Cotton.

The loosehead prop, wearing the number 1 shirt, has their head on the outside of the opposite tighthead at the scrum, and has to support the hooker as they try to move the opposing tighthead back and up.

On the other side of the front row, tighthead is where the money is at; with the amount of pressure going through their spines they earn every penny they’re paid.

At lineouts the props are generally the lifters but mostly they love the scrums.

In the old days the thought of a prop getting their hands on the ball more than once or twice a game would have attracted a funny look. Now they are used as ball-carriers in midfield and their handling skills have shot up. Mako Vunipola would (nearly) not look out of place at centre with his ball skills. Neither would Red Roses prop Sarah Bern.

Hooker (Number 2)

If the scrum-half is the gobby one in the backs, the hooker is generally the pack’s motormouth – impressive, seeing as they are totally defenceless at scrums with both their hands, and fists, wrapped around the props.

They are normally very feisty, as watching any old video of Brian Moore, Sean Fitzpatrick or Bobby Windsor will prove. Some, such as Daniel Dubroca and John Smit, even propped at Test level.

Throwing in at lineouts is a vital part of the hooker’s arts. Back in the day, some hookers regarded this part of the job as a sideshow and just lobbed the ball in willy-nilly. But with a wayward throw capable of killing an attacking opportunity – or even causing a defensive shambles – they take it rather more seriously now. You’d back current England captain Jamie George to hit double tops in the darts at Alexandra Palace.

One very famous England hooker once said he did his job if he scrummed well, hit rucks and threw in well at the lineouts. Those are the nuts and bolts but there is a bit more to it than that these days. The likes of Keith Wood helped to redefine the role, and they are now expected to pop up with the ball in hand, and do some fancy stuff.

Lock (Numbers 4 and 5)

Locks come in pairs but can be very different characters. Think about Bakkies Botha, the enforcer, and Victor Matfield, the lineout king, in the World Cup-winning South Africa team of 2007, or Martin Johnson and Ben Kay in the victorious England side of 2003.

All locks, or second-rows, have to be good scrummagers and good lineout jumpers; these are key parts of the job description. The hardest scrum merchant normally packs down behind the tighthead but both props feel a lot more comfortable if they have a good bit of power coming from the second row.

Some – such as Kay and current England head coach Steve Borthwick – are professors of the lineout, taking on responsibility for running that set-piece while trying to ruin the opposition’s. They must be strong maulers, and the longer their arms are the better for interfering and grappling for the ball in those situations.

It goes without saying that locks, like everything else in rugby it seems, are much bigger now than they were in the old days. Outgoing World Rugby chairman Bill Beaumont was an England and British & Irish Lions captain but at 6ft 3in probably wouldn’t get a look in at lock now. Maro Itoje at 6ft 6in is probably the perfect height, and wingspan, for a lock.

Back row (Numbers 6, 7 and 8)

The back row comprises three positions in rugby union. It is traditionally made up of the number 8, who packs down with their head between the locks at the scrum, and two flankers, the openside and blindside, who bind onto the locks at the side of the scrum.

The blindside packs down on the short side of the scrum, where there is less space available between the set-piece and the touchline. The openside patrols the open spaces. Some teams play left and right flankers, which requires all-rounders.

Opensides (number 7 in most countries but number 6 in South Africa), are the fetchers, and should be masters of the turnover, brutal tacklers and the link player in open play. Blindsides (usually number 6, except in South Africa), are the big hitters of the back row, which is why a lock such as Itoje or Courtney Lawes can often be found there. Having a big blindside also gives the team another lineout option, and they also have to look after the opposing number 8 as they run off the back of a scrum down the blind, or short, side.

The number 8 is the glory seeker of the back row, going for pushover tries, big carries in the midfield, destroying mauls and bashing up opponents. They can range from the ones who meander around the pitch but are always in the right position (Dean Richards in his pomp), or the more athletic, rangy lineout stars who are quick around the park (Kieran Reed).

The mix of the back row is a controversial topic. In the 1990s, when Jack Rowell was coach of England, the 5ft 10in Neil Back (who went on to win the World Cup at number 7) couldn’t get a look in. Rowell instead picked massive back rows, with the likes of Richards, Ben Clarke and Tim Rodber making up the unit. Back, perceived as too small, only got a regular gig when Clive Woodward took over.

Some sides have played two opensides together, making the breakdown a priority, as Australia did with Michael Hooper and David Pocock, while England World Cup winner Lawrence Dallaglio won most of his early caps as flanker before switching to number 8.

THE BENCH

Replacements (Numbers 16-23)

Impact players, game changers, finishers… coaches can describe their substitutes how they like but no player worth their salt wants to be on the bench from the start. This is the position in rugby nobody really wants.

A coach can name a list of eight replacements in rugby union and at elite level this has to include three specialist front-rowers. The bench has traditionally featured a 5:3 forwards:backs split, but in recent years World Cup-winning South Africa boss Rassie Erasmus has pioneered a 6:2 split (and even, on occasions, a 7:1 configuration) in order to unleash a “Bomb Squad” of fresh forwards in the second half of matches. Other teams have followed suit, though the 6-2 strategy can backfire if a back gets injured – as Wales learned to their cost in their recent Autumn Nations Series defeat to Fiji, when fly-half Sam Costelow was forced to play on the wing after an injury to outside back Mason Grady.

You’ll usually find a scrum-half among the substitutes, but a back who can play 10, 12, 13, 11, 14 or 15 is handy for one of the spots on the bench. These all-rounders usually end up cursing their versatility, however, as it means they are stuck among the replacements as cover rather than being a starter. Austin Healey, who was also a superb scrum-half, suffered a bit from this in England’s World Cup-winning team.

Download the digital edition of Rugby World straight to your tablet or subscribe to the print edition to get the magazine delivered to your door.

Follow Rugby World on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

[ad_2]

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source link