[ad_1]

A recent survey found that four in 10 players experience rugby-related stress urinary incontinence – Digital Vision/Klaus Vedfelt

There is a gym session that sticks in Rachel Lund’s mind; it was the time she saw a team-mate do a back squat and, out of nowhere, leaked urine. “It seems to be something that players just accept as the norm, when actually, it shouldn’t be the norm,” says Lund, a double Premiership Women’s Rugby winner with Gloucester-Hartpury.

Lund knows of many top-level women’s rugby players who have experienced stress urinary incontinence (SUI), the involuntary loss of urine during periods of intense physical exertion.

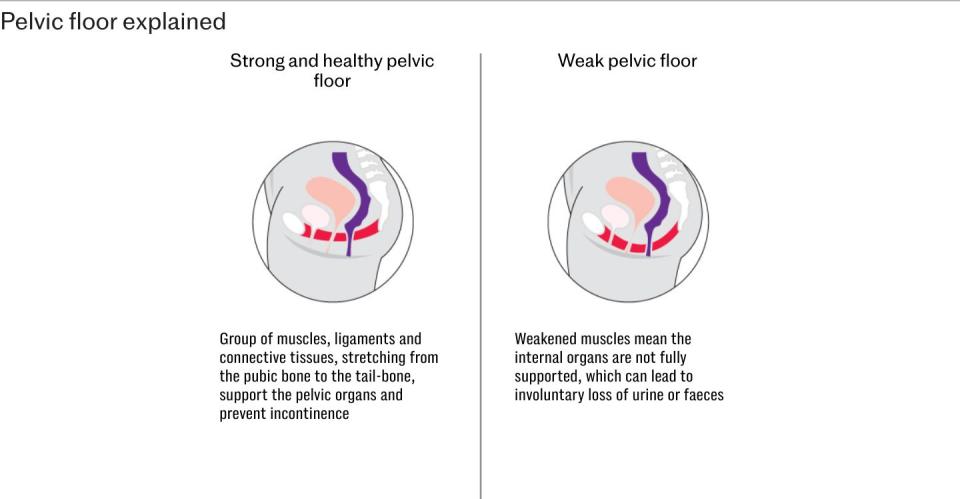

SUI is often thought of as an issue that impacts women who have gone through childbirth, when the pelvic floor – a group of layered muscles and connective tissues which support the pelvic organs – are stretched and damaged during labour.

But leaking urine can occur in women who have never been pregnant or given birth, and is particularly prevalent in those who participate in high-impact sports. Downwards pressure exerted on an unconditioned pelvic floor during physical activity can lead the muscle to dysfunction, with pain and difficulties controlling the bladder or bowel among the main symptoms.

Research published in the British Medical Journal last year found that four in every 10 players experience rugby-related SUI. Tackling, an event which creates significant intra-abdominal pressure, was the most likely cause for leaking urine, while running, jumping and landing were other contributing factors. Forwards had a greater risk of leakage because of their increased involvement in tackle events and a higher body mass index, which is linked to SUI in general populations.

Of those impacted by SUI in the study, which was based on 396 players, from community to elite level, almost three quarters perceived incontinence to negatively impact their performance.

“People think it’s normal to leak urine, but you shouldn’t just put up with it,” says Dr Izzy Moore, a reader in human movement and sports medicine at Cardiff Metropolitan University, who led the research. “Rugby is a physical game. Players aren’t just going to leak urine when they’re running – it’s often because they’re smashing into each other.”

So why are so many women experiencing incontinence on the pitch? And should rugby be doing more to confront this issue given it is impacting players’ self-esteem and confidence?

The covert nature of pelvic-floor dysfunction is part of the problem. Players are unlikely to report it because they feel embarrassed and it does not fit into rugby’s surveillance systems, which were traditionally designed for men.

“Similar to breast injuries, urinary incontinence doesn’t often create time loss, so players can continue and keep going,” says Moore, “but they have this health problem which doesn’t get recorded because by virtue of definition in our systems, they’re not missing training or missing a match.”

‘Think of the pelvic floor like a trampoline’

Men also have a pelvic floor, but it is structurally different to a woman’s – a female has three outlets whereas a man only has two – but it functions in the same way as any other muscle in the body.

“Think of the pelvic floor like a trampoline,” says Gráinne Donnelly, an advanced physiotherapist in pelvic health. “It should be stiff and responsive enough to absorb some load, but be able to bounce back. If it’s too stiff and tight, it’s not going to absorb load and it’s not going to be a good trampoline. But if it’s too lax and loose, it’s also not going to be a good trampoline.

“Either the muscles can be held too tense and, particularly with painful pelvic floor disorders, are being guarded or particularly held tight so they’re not being a good shock absorber, and that leads to leakage.

“If you hold your bicep all day, it gets sore and tired and it’s going to be too fatigued and sore to lift or do anything. The pelvic floor is similar – it doesn’t become as responsive and it doesn’t absorb that load.”

Alex Austerberry, the Saracens Women director of rugby, has seen first-hand how tackling – an event which Moore’s study identified as a key cause for leaking – has evolved over the past decade in the elite female game. “I’d suggest the top-end collisions are probably the same,” says Austerberry, who joined the London club in 2009. “But the volume of collisions has increased and we’re seeing more two-people in tackles. If we look at the GPS data, we can see the collision load is greater, and the ball-in-play time is greater.”

‘It’s more of a problem than people think’

Lund conducted her own master’s dissertation in rugby-related SUI two seasons ago. Surveying players in England’s Premiership Women’s Rugby competition, the results were startling. Out of 112 players, nearly two thirds (62 per cent) had leaked while playing. “I hypothesised that 17.5 per cent of the league in that year experienced stress incontinence,”says Lund. “One of the big things that really struck me was that players who were 10 to 12 years younger than me were experiencing it. It’s a lot more of a problem than people think.”

Gloucester-Hartpury’s Rachel Lund got some startling results in her university study of rugby-related stress urinary incontinence – SPP/Jay Patel

Periods were once considered sport’s greatest taboo, but the increased profile of female athletes has encouraged more open dialogue around menstrual cycles – yet the same cannot be said for incontinence, even if it compromises performance.

Telegraph Sport has learnt of just one PWR club who have used a pelvic health specialist – and Donnelly, who co-authored a pelvic health toolkit that was published on the Rugby Football Union’s women and girls wellbeing hub last year, believes the sport must do more to educate players about the importance of a functioning pelvic floor.

“A pelvic floor physio should be part of that multidisciplinary team,” says Donnelly. “Rugby players do strength and conditioning from head to toe, but not the pelvic floor. It could simply be that they haven’t adequately trained the pelvic floor to manage that level of load over the course of a training session or game.”

Lund echoes that sentiment – and warns against the women’s game professionalising too quickly without the adequate infrastructure underneath. She believes an easy way for clubs to begin prioritising pelvic floor health is by including it in end-of-season questionnaires. “There are some girls who are quite open about it, but I think actually, there’s probably quite a lot of girls that are secretly experiencing stress incontinence and don’t feel comfortable sharing it,” she says.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.

[ad_2]

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source link